MHServerEmu Progress Report: July 2025

We are now officially in the third year of development.

Player Manager

This month I fully focused on improving the server’s backend to make it possible to implement some of the long awaited social features, like parties.

As a reminder, in Gazillion’s architecture game servers are never directly exposed to the client. Instead, the client connects to a Frontend server, through which it establishes a connection to the Player Manager server. As far as the client is concerned, it communicates with the Player Manager. On the backend side one or more game servers are connected to the Player Manager, and the latter routes client messages to them. Overall it looks like this:

Because there is only a single “real” network connection, this entire architecture can be implemented as a single monolithic server. This is what we did for MHServerEmu, which is a single process, where the roles of individual servers are handled by what we call “services”. While not ideal in terms of horizontal scaling, this decision allowed us to make the server much easier to set up and run.

So far most of our efforts went into restoring the gameplay logic used by game instances, while our implementation of the Player Manager was mostly just scaffolding designed to get a single player into a game instance. There were some band-aid fixes to prevent the emulator from blowing up under load, like the current load balancing system used by public servers, where essentially multiple independent copies of the entire game are created to distribute the load. However, all of this needed to be rebuilt.

We have a pretty decent understanding of what the Player Manager’s responsibilities are supposed to be because one of the protocols for server-to-server communication was accidentally included in test center client builds for version 1.53. Here are the major ones:

-

Log clients in and out as they connect and disconnect.

-

Manage game and region instances across all game servers.

-

Orchestrate player transfers between game and region instances.

-

Route client messages to appropriate game servers.

-

Facilitate additional social features: social circles (e.g. friend lists), parties, and matchmaking.

Effectively, the Player Manager is the traffic controller for the entire game. This is overall similar to the functionality provided by online services like Battle.net in games like Diablo II.

The first order of business was overhauling how client management worked. Previously we would do this straight from network IO threads that invoked connect/disconnect events, but this caused all kinds of race conditions to happen all the time. I did quick fixes as issues arised, and eventually they all turned into a Rube Goldberg machine of locks, retries, and timeouts that was very hard to maintain, and it would still occasionally have minor problems. I replaced all of this with a producer-consumer style implementation, where various IO threads “produce” events, which are all “consumed” by a single worker thread. This not only eliminated the vast majority of race conditions, but also naturally lead to implementing a login queue system, which is crucial for making sure MHServerEmu can survive under loads heavier than what the server hardware can handle.

Our prior implementation of the Player Manager also did the work of creating and running game instances, which made things messy when services needed to communicate with game instances without going through the Player Manager, like the Leaderboard service. In addition, this made it harder to hypothetically separate game instances into a separate server process if the need ever arises. I have moved this functionality into a dedicated service, and the Player Manager now interacts with game instances using handles. While this somewhat increased the overall complexity of the system, it also made it a more accurate representation of the original server architecture.

With this the Player Manager now has a much more solid foundation for implementing new features, but some more work was required from the game server side of things.

Game Threading

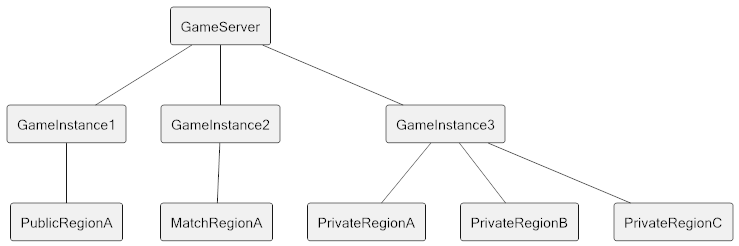

Although Marvel Heroes was marketed as an MMO, its world structure is really an extension of the system that was used in Diablo II. The world consists of a number of game instances, and within each game instance there is one or more regions. What creates the illusion of a unified world is how you transfer between these instances: rather than picking a game from a list in a Battle.net interface panel, you automatically exit one game and enter another when you click on a transition entity in the game world. Some regions are designated as public, which means public game instances are created to host them, while others are considered private, and they are hosted by a private game instance the belongs to a specific player. There are also match regions that can behave as public or private depending on what the player who creates them chooses. The overall structure is supposed to look like this:

Our initial quick and dirty solution was to have a single game instance to host all regions with a dedicated thread to process it, which is more like how single player games are usually made. Eventually I added the functionality to increase the number of instances to allow public servers to handle more load, but the overall system remained the same, and the number of threads matched the number of game instances. In order to implement parties we need to replicate the original system, because what joining a party actually does is provide other players access to the leader’s private game instance. However, doing it means drastically increasing the number of game instances from just a few to potentially hundreds. Having dedicated threads for every single game instance would cause all sorts of performance issues, so we needed another solution for threading.

We now have a dedicated pool of worker game threads that can process an arbitrary number of game instances. This uses the same basic idea as the producer-consumer pattern, but game threads act as both producers and consumers. Work is scheduled via a time-based priority queue: when a game instance finishes its tick, it calculates the time when the next update should happen, and this time is used as the priority for the priority queue. This queue is shared by all worker threads, so any of them can potentially do the work. Threads go to sleep when there is no work.

This new implementation not only decouples the number of game instances from the number of threads, but also allows us to potentially have more granularity in how regions are processed. Some regions, like Cosmic Midtown Patrol when it is full of players, can take significantly more time to process than something like a terminal region with a single player in it. When multiple “heavy” regions are in the same game instance, processing all of them may take longer than the target frame time of 50 ms. Not hitting this target manifests as lag, and “light” regions end up having to wait for the thread to process all the madness happening in “heavy” regions first. This is one of the main causes of lag that you can occasionally see on public servers during prime time. Once regions are distributed across game instances as planned, “heavy” regions may still lag if things get too crazy, but they will no longer bring other regions down with them, as long as there are not too many of them.

Region Transfers

The new threading system enabled us to potentially have many more game instances, but there is still the issue of how you actually move a player from RegionA in Instance1 to RegionB in Instance2. There are many things that can potentially cause a player to move from one region to another:

-

Clicking on a transition.

-

Selecting a region in the waypoint menu.

-

Using the bodyslider.

-

Triggering a mission action or a MetaGame state.

-

Resurrecting after dying.

-

Teleporting to a party member.

-

Activating Prestige.

In order for the Player Manager to be able to orchestrate this, it needs a common API for initiating all of these transfers from gameplay code. Unfortunately, we accumulated some technical debt on this front as well, and it needed to be cleaned up before we could proceed.

One of the more egregious troublemakers with this has been the direct transition system. This refers to portals that are bound to specific region instances. Originally they were implemented for “bonus levels”, like the totally non-existent Classified Bovine Sector, but later on direct transitions were also used for the Danger Room mode. Danger Room in particular has been a major source of headache, because each “floor” in this mode is its own separate region. There is also an intricate data plumbing system that transfers properties from the item that opens the portal to the portal itself, and then through all subregions.

While working on this, I have also discovered that one of the assumptions I had about the region transfer process was actually a misconception. I previously believed that we had to do the full game exit procedure on every region transfer, which involves destroying and recreating all entities owned by the transferring player, including all avatars and items. The main reason for this was that reusing the same player entity caused all sorts of issues with the client, including completely breaking the inventory grid. However, as it turns out we can reuse the same player entity, as long as we just remove the avatar entity from the game world and never let the player entity actually exit the game. There is subtle difference between the two, but it results in us not triggering any of the critical issues client-side and saving some resources server-side.

These backend improvements require significant changes to the fundamental systems that have not been really touched in quite some time, so weird issues can pop up, and everything needs to be thoroughly tested before proceeding with the next step. One example of such weird issue was a bug where resurrecting in the Fisk Tower terminal would teleport the player to the pre-update story version of the Fisk Tower region.

At the time of writing this, the stage is almost set to make the final seismic shift by implementing seamless transitions between game instances. Once this is done and tested, I will be able to work on social circles and parties.

This is all I have for you today. See you next time!